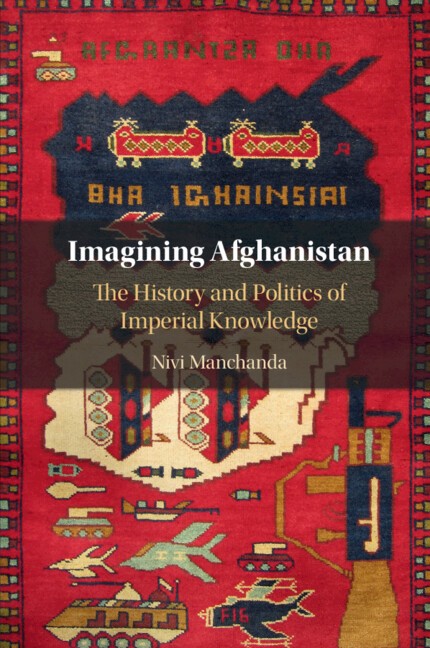

Quite a number of books have followed in the tradition of Edward Said, critiquing and contesting the manufacturing of narratives. Nivi Manchanda's "Imagining Afghanistan" The History and Politics of Imperial Knowledge" (2020) provides a deep dive into those narratives of Afghanistan. Chapters of the book explore the use of "tribe" and "tribalism", the colonial construction of narratives, the American military deployment of narratives, the portrayal of "warlords" and women in Afghan society, as well as masculinity and sexuality. For anyone interest in this topic, this is a rich book of details. In the specific, readers familiar with this tradition of writing will find a similar meta-narrative. A few notes:

The book: "partakes in the effervescent conversation about social science's implication in empire, both past and present, and brings to the table a rather peculiar example of this implication. This is the story of imperialism in Afghanistan, a story which is perhaps best designated as that which is the 'same but different'. It is the 'same' in that it displays, even exemplifies, a steady, if not quite consistent, lineage of colonial thinking about the Other." (p. 5-6)

As reported elsewhere, but in more detail here: "What the exhibition and its curators fail to mention is how these textbooks came into being. During the mid 1980s, a project funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) printed millions of textbooks in Peshawar that were distributed to schoolchildren across Afghanistan. The textbooks were designed to indoctrinate Afghans against the evils of the Soviet Union and made for immensely powerful propaganda. Specialists from the Afghanistan Center at the University of Nebraska Omaha received $51 million to develop a curriculum, which glorified jihad, celebrated martyrdom and dehumanised foreign invaders. Published in Dari and Pashto, these schoolbooks taught the alphabet through Kalashnikovs and counting through guns and bullets, and had elaborate mathematical questions which drew on conflict scenarios, deploying various firearms in inventive ways, for more advanced pupils. One example read: 'A Kalashnikov bullet travels at 800 meters per second. A mujahid has the forehead of a Russian in his sights 3,200 meters away. How many seconds will it take the bullet to hit the Russian's forehead?' Although USAID funding for the project stopped in 1994, multiple copies of the texts remained in circulation in the 1990s and into the 2000s." (p 2-3)

Continues later: "… Center for Afghanistan Studies at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, founded in 1972, is still the world's only permanent research and training centre devoted solely to the study of Afghanistan.24 Set up to counterbalance the Soviets, following a lull in the 1990s, it found a renewed sense of purpose after 9/11. The centre has since provided 'training on Afghan history, culture, and language to U.S. Army Human Terrain System teams that were departing for Afghanistan'. It has trained over 600 military and civilian personnel to prepare them for service in Afghanistan. It also helped 'professionalize' members of the Afghan National Army between 2008 and 2010.25 Similarly, Indiana University recently inaugurated a National Resource Center for creating Pashto-language materials, focusing on providing 'key training for U.S. forces in Afghanistan'. Gene Coyle, a retired CIA officer, who has never worked in Afghanistan, serves as director…" (p. 9)