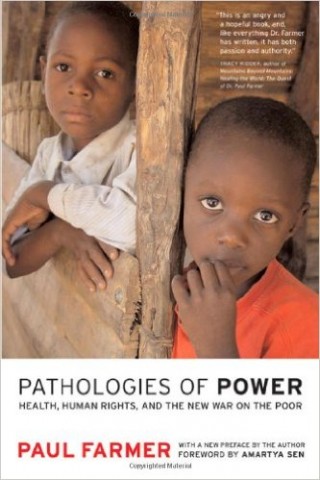

Pathologies of Power

Paul Farmer's (2005) "Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor" is a "physician-anthropologist's effort to reveal the ways in which the most basic right – the right to survive – is trampled in an age of great affluence" (p. 6). However, Farmer covers much more than the right to survive, this book "is about the struggle for social and economic rights, the neglected stepchildren of the human rights movement. Because social and economic rights include the right to health care, housing, clean water, and education, they are sometimes called the "the rights of the poor."' (p. xxiv). It is highly recommended for academics and practitioners, and I also highly recommend Farmer's book Infections and Inequalities.

For those new to development studies, academics who assume development practitioners are non-reflexive positivists, and for practitioners looking to be more critical of the processes within international development, Farmer's books are essential reads. In the opening pages he sets the tone: "It was not the silence that rankled. It seemed to us that the exercise was demeaning – the participants, having survived genocide and displacement, were now being treated like children. They were being asked to respond to an agenda imported from capital cities, from do-gooder organizations like ours, from U.S. universities with the "right" answers to their every question. No harm done, perhaps, and the topic was important – but how helpful was this exercise, with its aim of changing the mentality of the locals, who were, after all, the victims of the previous decades of violence? A change in mentality was needed, certainly, but it was needed in the hearts and minds of those with power – and they were not here" (p. 3-4).

It is not just the 'others' with power; as a physician, Farmer writes that many "physicians are uncomfortable acknowledging these harsh facts of life and death. To do so, one must admit that the majority of premature deaths are, as the Haitians would say, "stupid deaths." They are completely preventable with the tools already available to the fortunate few" (p. 144). Yet, it is not simply more "development" that is required: "Developmentalism not only erases the historical creation of poverty but also implies that development is necessarily a linear process: progress will inevitably occur if the right steps are followed. Yet any critical assessment of the impact of such approaches must acknowledge their failure to help the poor" (p. 155)

Weaved throughout the book, Farmer expresses his concern with a changing set of norms and values: from rights, respect and dignity to costs and value for money. He writes: "many of the concepts currently in vogue in public health – from "cost-effectiveness" to "sustainability" and "replicability" - are likely to be perverted unless social justice remains central to public health and medicine. A human rights approach to health economics and health policy helps to bring into relief the ill effects of the efficacy-equity trade-off" (p. 18). This view is not just challenged as an opinion, but as an affront to the practice of health care: "the flabby moral relativism of our times would have us believe that we may now choose from a broad menu of approaches to delivering effective health care services to the poor. This is simply not true. Whether you are sitting in a clinic in rural Haiti, and this witness to stupid deaths from infection, or sitting in an emergency room in a U.S. city, and this the provider of first resort for forty million uninsured, you must acknowledge that the commodification of medicine invariably punishes the vulnerable" (p. 152). This book was published in 2005, and parts published earlier, and Farmer foresaw a challenge that has grown (while also shifting names from cost-effectiveness to value for money, to assessments of quality-adjusted life years, and as metrics in results and impact reporting): "As international health experts come under the sway of the bankers and their curiously bounded utilitarianism, we can expect more and more of our services to be declared "cost-ineffective" and more of our patients to be erased. In declaring health and health care to be a human right, we join forces with those who have long labored to protect the rights and dignity of the poor" (p. 159).

For those who work with marginalized and vulnerable people, who voices are excluded, it is challenging to convey experiences to others. In Farmer's earlier book Infections and Inequalities he used vignettes of people's lives as an attempt. In this end, however, "the experience of suffering, it's often noted, is not effectively conveyed by statistics or graphs. In fact, the suffering of the world's poor intrudes only rarely into the consciousness of the affluent, even when our affluence may be shown to have direct relation to their suffering. This is true even when spectacular human rights violations are at issue, and it is even more true when the topic at hand is the everyday violation of social and economic rights" (p. 31). It is both a depressing conclusion – the reality of a lack of concern – and a call to action. The systems that create and entrench poverty, as well as those that ignore suffering when plan to see, will continue lest things change, and change necessitates informed, critical engagement.