I try to keep an eye out for useful teaching materials, particularly ones that provide unique perspectives on issues that students may not have encountered in their studies (unfortunately many courses are similar ideas/voice on repeat, in various forms). "Critical Development Studies: In Introduction" (2018) by Veltmeyer and Wise is brief (170 pages), easy to read (lots of lists), and accessible (first year undergrad level). While not a "sharp edge" of critical studies per se, it provides a counter narrative to the dominant discourses. The unique offering is (largely) a vantage point from Latin America.

A couple of quotes for insight into the book:

"There are three fundamentally different ways of understanding 'society': as a collection of individuals, each motivated to better themselves or to seek self-advantage; as a system of institutionalised practices that sets rules and limits to the action of individuals; and as a system of overlapping and interconnected social groups with shared experiences and identify which enable them to act collectively in the struggle for social change. The first way of understanding society is widely shared by economists and political scientists in the liberal tradition. For the sake of analysis they see the individuals as rational calculators of self-interest, or as citizens who are equal in their opportunities for self-advancement, and as the fundamental agents of social change. The second and third ways of understanding society and the development process relate to what could be described as the 'sociological perspective'—the view that the problems, experiences and actions both of individuals and nations can and must be related to the potion that they occupy in the broader system, and understood in terms of the way society or the economy is organised and structured." (p. 54)

"From a critical development perspective (that is to say, one that questions neoliberal institutionality and the structural dynamics of capitalism in order to promote development alternatives that benefit the majority of the population), sustainable human development is understood as a social construction process that starts by creating awareness: the need for change, organization and social participation in order to generate a popular power that can then strive for social emancipation. This involves the eschewal of socially alienating relations that deprive people of their merits, destroy the environment, and damage social coexistence." (p. 118)

Book review: Kelly, Anthony and Westoby, Peter. 2018: Participatory Development Practice: Using Traditional and Contemporary Frameworks.

There is an emerging recognition that many of the ideas, practices and approaches within development studies and practice can replicate colonial attitudes, be paternalistic and disempowering, and may entrench marginalization. The emergence of a wide array of participatory methodologies has in part been in response to these challenges, however they too struggle and despite an ethos that aims to create new pathways have not been a panacea. In Participatory Development Practice, Anthony Kelly and Peter Westoby build both on their depth of experience as well as their grounding in the Gandhian tradition, to facilitate a rethink of a range of 'how' questions. A key concept throughout the book is relationships; with oneself, between individuals, within groups, in an organizational structure and culture, in coalitions of organizations and in engaging with the world. This book offers ideas, practices and approaches, that provide avenues for critical reflection and new forms of practice. For students, workers and practitioners who find themselves asking 'how could we do this better?', this is a work full of insight. 'Framework' in the title might suggest a checklist, instead what this framework offers are multiple levels of introspection, of doing and being better. Participatory Development Practice is a book for everyone working alongside others who want to gain deeper connections and to build stronger relationships. This is, the authors argue, the root of it all. People are lost in projectized development. What needs to change are the layers of relationships that build, guide and direct development action.

The chapters of the book are structured around levels of participatory development practice (individual / self, micro, mezzo, macro, and meta methods). The emphasis on the self as well as macro and meta are valuable additions to the participatory practice dialogue as often participation is framed in the micro and mezzo spheres. Each chapter outlines respective methods in a clear and thought-provoking fashion, which they present as being interconnected and facilitating purposeful and systematic practice. While informed by theorists throughout, the ideas of theory are presented in an accessible way with relatable examples. At its core, the book outlines pathways for how development can be oriented to be human-centered or people-centered, offering practical ideas, practices and provocations to do so.

While outlining a framework, and a wide range of principles and steps, Participatory Development Practice is grounded in a call to reflect on character traits, akin to calls made by Robert Chambers. In this regard, participatory development practice is about what we do, but more importantly is it about how we do it. Better tools are important, but Anthony Kelly and Peter Westoby also call us to be better people; working with humility, integrity, commitment, openness and honesty (what the authors call principles). In the concluding remarks, the authors specifically explore how we can cultivate gentleness, reflect on motivations and commitment and foster comradeship. These values and traits permeate the book. In Chapter 2, the "implicate method" the authors explore positioning oneself, and frameworks of doing so, with examples being drawn from Gandhi, McCauley, village workers in India and Fanon. Introspection continues in Chapter 3, as the authors explore questions of relationships and dialogue, building on Tagore, Buber and Freire. In this regard, Kelly and Westoby have offered something quite unique, these traits are not prefaces but are the process; the means being the end, the end being the means. The framework and various processes are not technical ones, but of cultivating relationships, traits, skills, ideas and principles.

In a recent review of Chambers' Can We Know Better (2019), I reflected on the dichotomy between mechanical, 'expert-driven' approaches (e.g. fiscal policy, standards for regulating environmental toxins) and participatory approaches (Cochrane, 2018). This is because learners often grapple with which approaches to apply when, and for which challenges. Kelly and Westoby make a useful distinction between service delivery (health, education, water, electricity, transportation, communications, public safety) and participatory development. The former, they argue, has failed those who most need it, often passing them by and leaving them behind. They state that "service delivery on its own fails the poor" (p. 15). Instead, they argue that there needs to be a new pathway; "a different type of program delivery whether the programme is about livelihood, health, education or any other matter of importance to the people" (p. 15). The answer is the participatory approach, "which involves people doing things for themselves" (p. 16). The self-help ethos and bottom-up framework is laudable, but also raises questions. Is it just? In so doing, are we tasking the most marginalized and vulnerable with the roles and responsibilities of government? And, conversely, are we reducing the accountability of government to be more inclusive and respectful the rights of all? In wondering about where these lines are drawn, Green's (2012) book on active citizens and effective states may provide some balance. However, there are also other questions of ethics that could be asked: Might a bottom-up approach neglect historical injustice and calls for distributive justice? The authors describe participatory work as equality-driven, but ought not the question also be one of equity, which would necessitate the involvement of different actors, specifically challenging questions of power and privilege that may lie beyond the community? The authors might suggest that fostering the kind of relations they speak of in the book may lend to that. The historical experience, including of those theorists the authors rely upon, suggests different configurations, scales and actors may be required for the desired change to come about. While the authors do not raise these questions, they are cognizant of the challenges. The book navigates between a critique of the failures of service delivery as well as its potential as a pathway to improve the human condition (p. 17).

This book will be a valuable addition for students, workers and practitioners because it presents complex ideas in clear ways with relatable examples. Far too often theory in inaccessible, or the direct linkages to practice are challenging to tease out. Kelly and Westoby have made these ideas accessible as well as actionable. Participatory Development Practice is suitable not only for undergraduate courses in development studies but also for the broad array of workers and practitioners seeking to make their communities better places.

References

Cochrane, L. 2019. Book Review: Chambers, Robert. 2017. Can We Know Better? Reflections for Development. Progress in Development Studies 19(1): 84-86.

Green, D. 2012. From Poverty to Power: How Active Citizens and Effective States Can Change the World. Practical Action Publishing: Warwickshire.

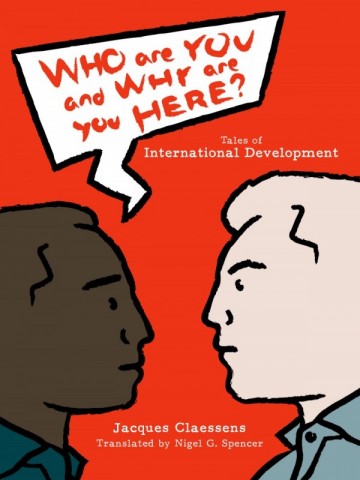

I have previously noted my interested in the expanded journal version of people recounting their experiences (e.g. this recent book on the Ebola response). The style (and title) of Jacques Claessens "Who are you and why are you here?" (2018), which was originally published in French in 2013 and translated in this version by Nigel G. Spencer, looked appealing. While interesting, I did not as much enjoying the fictionalization of the book. At least for me, this reduced the interest that I typically have of first-hand personal narratives. The book does open some doors and windows into problematic behaviours and decisions in the sector and might be a starting point for discussions, particularly for those unfamiliar with the sector.